Read on Daily Maverick

Dirty politics, ‘rogue unit’ suspicions — the case of convicted ex-Crime Intelligence officer Paul Scheepers The recent conviction of former Crime Intelligence officer Paul Scheepers for fraud, money laundering and contravening surveillance and private security legislation now brings into question the motives and veracity behind his previous work. The case also edges close to other ‘rogue unit’ accusations.

Gangsters in government: State Capture parallels between South African and Bulgarian criminals Criminals who infiltrate governments often try to make their honest colleagues look corrupt to deflect from their own dirty actions. They also turn on journalists exposing them. This is a trademark of State Capture and another murky element linking South Africa to Bulgaria.

Ex-cops in the cross-hairs – they face death threats, but say their SAPS bosses have abandoned them Since the killing of a top detective, former officers have been alleging that the authorities are not doing much to protect them from threats linked to organised crime – and sometimes to their colleagues.

Rogue, rogue-er, rogue-est — dissecting (real/fake) claims of cops colluding with criminals “There are layers of claims, from national to city level, of crooked law enforcers working against their honest colleagues, especially in South Africa’s gang capital, the Western Cape. This is rattling, more so when viewed through the lens of a cop’s assassination.”

To serve and endanger: Corrupt cops are South Africa’s greatest security threat “When police officers fear for their lives, claim certain colleagues are targeting them and colluding with criminals, and sometimes even arming assassins, where does this leave us? The short answer — in a tightening spiral where our security is constantly eroded and where those who try to expose the rot from within put their very lives at risk.”

In SAPS veritas — how the ‘dangerous’ police firearms control offices symbolise a service in crisis The cops’ Central Firearm Register is in the ‘collapsing’ Veritas building in Tshwane. This is ironic because translated from Latin, ‘veritas’ means truth but corruption claims tail the firearm register. The building’s perilous state also seems to reflect the true state of the South African Police Service.

Cops and Whoppers: The claims and counterclaims dogging Cape Town’s police

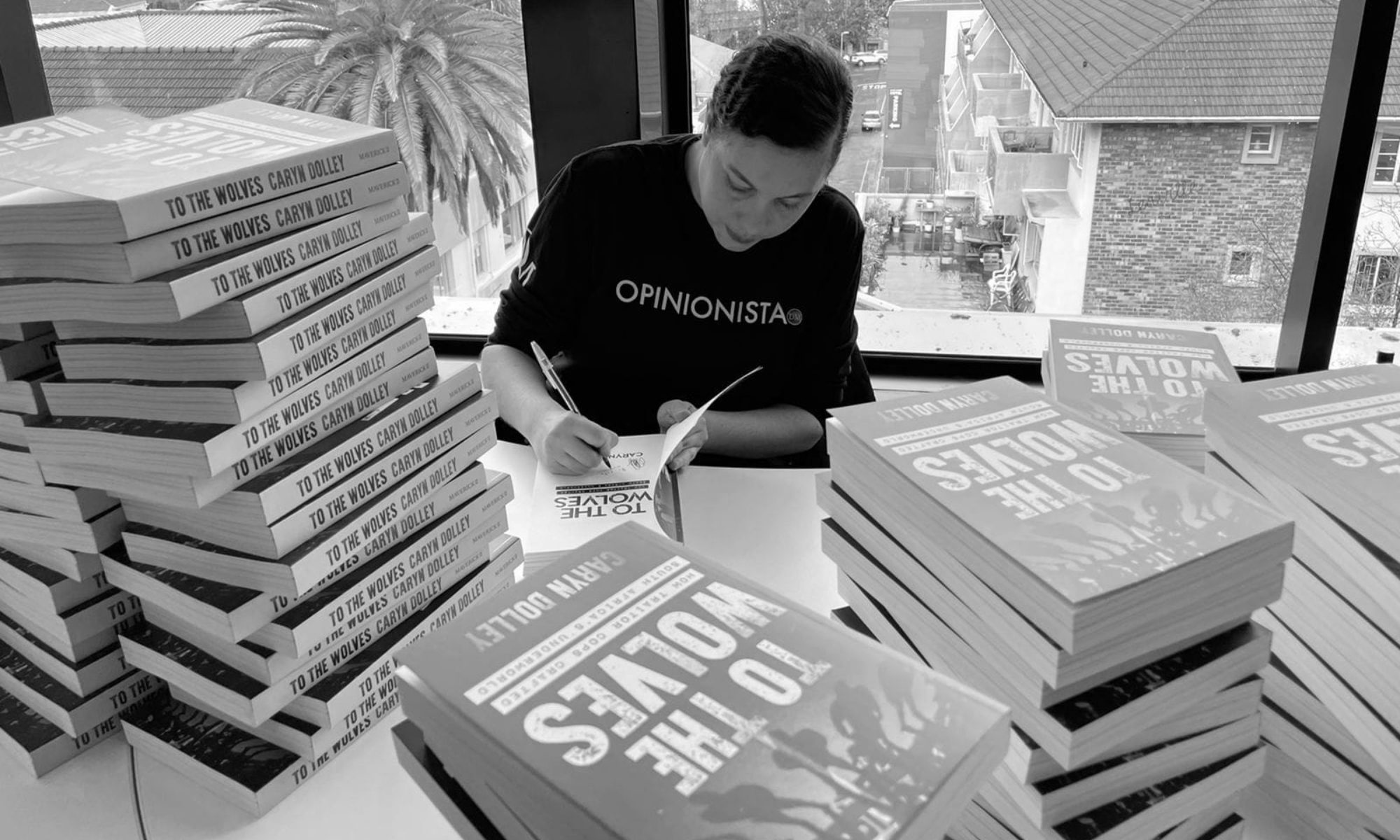

The Enforcers: Inside Cape Town’s Deadly Nightclub Battles was published in June 2019.

One of the core aspects it focused on was how, over decades, police officers have been pointed to as not only trying to smother the city’s underworld, but also of bolstering it.

When this particular analysis piece was typed up, a year had gone by since the book was published and this arena, an entanglement of claims and counterclaims, had become even wilder.

Here some claims involving police officers, and how these lock into more dated claims, are unpacked.

But these ping-ponging accusations often detract, sometimes by design, from other dubious happenings and the harsh reality many Cape Town residents (some still in the womb) are forced to try and survive.

This copy is therefore interspersed with stories, sourced from news sites, that focus on horrendous incidents that have become viewed as regular, but which are absolutely irregular. The only regular aspect is the backdrop of high-level deceit underpinning these traumas.

Cape Town is home to some of South Africa’s most notorious gangs. It is also home to a police service creaking under mounds of claims that some officers are furthering, not fighting, crime.

This has been the case for many years.

For clean cops, this means that aside from possible crooks within their ranks, and those operating externally of the police service, they are also up against the perception that they are dodgy.

While they try to tackle this triple burden, their truly corrupt counterparts slink between accusations, claims and counterclaims, some of which they themselves (or via operatives under their control) may peddle to deflect from their own dubious deeds.

This produces a concoction that truly stains policing.

It is a shame because these stains spread and blot out hopeful notions of a protective layer buffering law-abiding residents from criminals.

This protective layer is utterly necessary for Cape Town that has been the scene of a string of successful and failed assassinations, and of stray bullets killing and maiming children.

- 2 young children killed in separate shootings in Cape Town published by Eyewitness News on 16 June 2020.

- Toufiek, 7, comes home with a bullet published by Daily Voice on 12 June 2020.

- Innocent Cape dad shot 18 times in drive-by shooting published by IOL on 10 June 2020.

- [WATCH] Brian keeps fighting: ‘Brain dead’ teen defies the odds to celebrate his 17th birthday published by Daily Voice on 8 June 2020.

This overall situation would seem less dire if it were only residents wary of some cops, but police officers themselves are wary of colleagues.

‘They set me up’ – a cop’s perspective

In 1996 police officer Andre Lincoln was tasked with heading an elite investigative task unit.

During apartheid Lincoln was an ANC operative involved in underground umKhonto weSizwe activities.

By 1996, under the fresh democratic presidency of Nelson Mandela, he was heading the special task unit and investigating individuals including Cyril Beeka and Vito Palazzolo.

Beeka had dominated nightclub security operations in Cape Town in the 1990s – some police officers suspected these activities were a front supported by apartheid-era cops and Beeka was suspected of using intimidation and extortion to maintain his security stronghold.

Palazzolo, then based in Cape Town, was believed to be a high-ranking member of the criminal organisation Cosa Nostra. He was also suspected of having South African government officials on his payroll.

The Lincoln saga involves layers of accusations and legal processes that have dragged on for more than two decades.

In 1997 the investigative unit he was heading was effectively labelled as a rogue one.

Then in 2002 Lincoln, who some believed was working with and not against Palazzolo, was convicted of 17 of 47 criminal charges.

But Lincoln insisted that apartheid-era cops had effectively framed him to stifle the investigations he was busy with.

- Pregnant woman shot dead in her Cape Town home published by News24 on 27 February 2020.

- Five-year-old shot and killed in Cape Town published by SABC News on 21 December 2019.

- Pregnant Manenberg woman shot eight times published by IOL on 18 August 2019.

In 2003 he was discharged from police and six years later, after more legal wrangling, he was acquitted of the convictions.

Lincoln was reinstated into the police in 2010 and eventually, in 2018, was successful in a lengthy civil case against the Police Minister which concluded with the finding he had indeed been maliciously prosecuted years earlier.

This added weight to Lincoln’s claims that he had been framed.

But the police ministry appealed this finding and in June 2020 it was successful – the Supreme Court of Appeal found that the prosecution against Lincoln had not been driven by malice.

Lincoln, despite having been up against police top brass in court, was still viewed by them as a thorough policeman – by this point, he had been appointed head of the Anti-Gang Unit.

‘They set me up’ – an accused’s perspective

Back in December 2017 businessman Nafiz Modack and four other men were arrested for allegedly using intimidatory tactics and extortion to secure a security contract at a Cape Town restaurant.

Some police officers viewed Modack as continuing the operations of Cyril Beeka (who had been assassinated in Bellville South in March 2011).

During the bail application phase of the Modack-focused extortion case, a police officer had described Modack’s alleged activities as mirroring Beeka’s.

It had also been claimed in court that controversial businessman Mark Lifman – who police viewed as a rival of Modack’s – controlled some cops, especially the group that had arrested Modack.

Eventually, the lengthy extortion case against Modack and his co-accused ended in acquittals in February 2020.

In early June 2020 it emerged that Modack wanted to claim roughly R10m damages from among others, the Police Minister, as he believed he had been falsely charged in the extortion case.

- Moms march for their murdered children published by GroundUp on 1 August 2017.

- ‘She smiled at me’ – dad recalls the moment he realised baby Zahnia had been shot published by News24 on 8 October 2018.

- Family grieves death of boy killed in Delft gang crossfire: Four-year-old Machiano Geswind was standing in front of his home when he was hit by a stray bullet published by Eyewitness News on 1 June 2016.

This surfaced just days after the Supreme Court of Appeal had ruled against Andre Lincoln.

In the Modack matter, he believed the investigating officer in the extortion case, Lieutenant Colonel Charl Kinnear, had acted together with Lincoln and Western Cape detective head Major General Jeremy Vearey, to arrest him, even though there was not sufficient reason for this.

Kinnear is a member of Lincoln’s Anti-Gang Unit.

Vearey has a similar political history to Lincoln.

He has weathered several accusations that he is involved in organised crime and he has before claimed that crime intelligence and police officers in cahoots with gangsters have tried to tarnish his reputation via smear campaigns to derail investigations he has headed.

Vearey was one of the police officers who steered a massive national investigation that revealed cops were channeling firearms to gangsters in Cape Town, in what became known as the guns-to-gangs case. About 1 066 murders were believed to have been carried out with the smuggled firearms.

Vearey claimed politics had derailed this investigation, which started in 2013 under the Jacob Zuma presidency, and that it had also resulted in his effective demotion.

In any event, in June 2020 Modack pushed to try and claim damages from the Police Minister, as well as police officers including Lincoln, Vearey, and Kinnear, for what he claimed was his wrongful arrest.

Days after Modack publicised his intention to try and sue them, he was arrested in Johannesburg on fresh charges relating to firearms.

Eight police officers, as well as two ex-cops, were also taken into custody.

The case, the culmination of a three-year investigation, had to do with alleged irregularities at the Central Firearm Registry and involved at least 21 people.

“Police received information on alleged fraud and corruption relating to firearm licence applications taking place between Cape Town and Gauteng,” a police statement said.

“It was found that several people including Cape Town underworld figures and their family and friends allegedly obtained their competency certificate/s and firearm licence/s to possess a firearm… in an allegedly wrongful manner.”

(These claims mirrored allegations in a splinter case stemming from the guns-to-gangs investigation Vearey had helped head. In the splinter case, which dates back to 2014, former Central Firearm Registry police officers and suspected 28s gang boss Ralph Stanfield had allegedly worked together.)

Lincoln, as head of the Anti-Gang Unit, had played a key role in the June arrests of Modack and the cops.

‘They are setting us up’ – another cop’s perspective

Kinnear, who had been the investigating officer in the initial big case against Modack, the extortion case, had submitted a complaint to his superiors about fellow cops back in December 2018.

He claimed that five police officers linked to the Western Cape’s crime intelligence unit were misusing state resources for personal reasons, but under the guise of investigating him and four colleagues including Vearey.

Kinnear claimed that Modack, via an advocate, had once referred to information Kinnear had conveyed to others.

“The only way that Nafiz Modack could have such information would be should have been given the information by someone from Crime Intelligence who were ‘illegally’ listening to my telephone lines,” (sic) Kinnear had stated.

He had therefore implied that an officer linked to crime intelligence was in cahoots with Modack.

In a January 2019 communication in response to Kinnear’s complaint, the head of the country’s crime intelligence, Lieutenant General Peter Jacobs, found that the group of officers Kinnear had complained against was “a rogue team.”

Jacobs had called for it to be disbanded.

The links between the claims and counterclaims

Kinnear, Lincoln, and Vearey have each claimed that other police officers have targeted them.

In his complaint, Kinnear listed five police officers as being targeted by a group of police officers with links to crime intelligence. He also effectively pointed to some officers as being aligned to Modack.

In a draft letter relating to Modack’s intentions to try and sue for damages, four of the same officers who Kinnear said were being targeted were named as being involved in Modack’s arrest, which Modack claimed was unlawful. It was also previously claimed the group of officers involved in Modack’s arrest was controlled by businessman Mark Lifman.

This all creates the impression that there are two police factions in Cape Town.

Then there are the links and parallels between Modack and Lincoln.

Lincoln previously claimed police officers had maliciously orchestrated a criminal case against him and later he pushed to claim for damages relating to this.

Modack is now claiming a group of police officers, among them Lincoln, effectively orchestrated a criminal case against him and Modack is now pushing for damages.

Lincoln once investigated Cyril Beeka, a rumoured intelligence operative.

Modack was viewed by some police officers as having continued Beeka’s security-related operations and Modack denied rumours that he was an intelligence operative.

Lincoln, as head of the Anti-Gang Unit, played a key role in in the investigation into, and arrests of, Modack and police officers in the firearms case of June 2020.

- Nine-year old shot dead in Lwandle published by eNCA on 8 August 2014.

- Grade one W Cape child shot on first day of school published by Mail & Guardian on 16 January 2014.

- ‘Miracle’ mother relives slayings: ‘Liezel van Heerden was 15 at the time and pregnant, was shot 24 times, but she and her unborn child survived’ published by Cape Times on 12 August 2011.

No man’s land

Rooting out truth from deceit, good cops from bad cops, and true whistle-blowers from sham information peddlers is difficult because these elements are being buried under an ever-growing mound of claims and counterclaims.

Those with pure intentions trying to expose the truth are getting lost in this.

These opaque battles rooted in Cape Town and stretching further afield are much deeper than what usually surfaces into public sight. Those pulling the strings are undoubtedly politically powerful and moneyed.

The physical extent of gang fights in Cape Town can be gauged by a victim count, but the cost and impact of infighting and corruption among police officers cannot be measured (character assassination does not directly contribute to a murder toll).

Gang battles are indeed a tangible symptom of broader organised crime.

Claims among and against police officers form an invisible cage that traps residents between a pressing layer of intense mistrust in cops and this overt violence.

Those who are burying the truth, peddling false accusations and tarnishing the good reputations and work of decent individuals, are reinforcing this cage.

See the next page for a detailed analysis of interlinked shootings in Cape Town.